Share This Page

Share This Page| Home | | Sailing | | Alaska 2010 | |  |  |  Share This Page Share This Page |

Copyright © 2010, P. Lutus. All rights reserved. Message Page

| Prior years: |

Alaska 2002 |

Alaska 2003 |

Alaska 2004 |

Alaska 2005 Alaska 2006 | Alaska 2007 | Alaska 2008 | Alaska 2009 |

(double-click any word to see its definition)

Those who regularly read my Alaska articles know I rescue a lot of boats. This year I tried to rescue a really, really big boat, with only modest sucess. Here's the story.

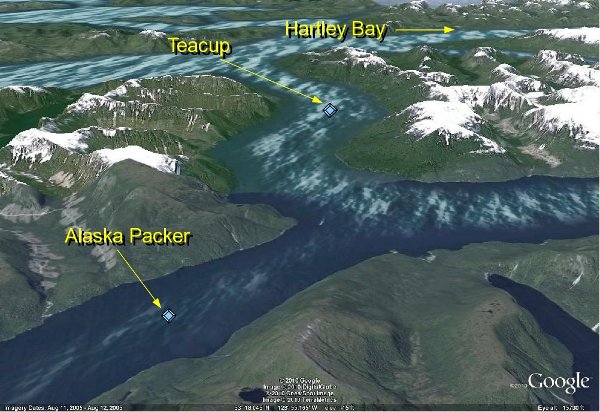

On April 25th, as I made my way along the Inside Passage in British Columbia, I heard an emergency call from what turned out to be a very big boat — a 338-foot, 4,042-ton (that's over eight million pounds) fish processing boat named "Alaska Packer." I quickly established that the stricken vessel was only eight nautical mies away, so I reversed course and advised the Coast Guard that I would be on the scene shortly.

At the same time, some vessels in Hartley Bay (see picture, about 20 nautical miles away) also responded and got underway. Hartley Bay is a town located pretty much in the middle of nowhere, but near an important nautical route, the equivalent of a highway in British Columbia.

The people in Hartley Bay are always ready to help vessels in distress, in fact they were essential to the rescue of about 100 passengers and crew of the ill-fated Queen of the North, a large ferry that strayed off course, crashed into rocks and sank in March 2006.

No one who reads about the Queen of the North sinking can have any doubt that the passengers and crew owe their lives to the people of Hartley Bay, who, on hearing a call for help, dropped their forks and coffee cups, launched their boats, arrived after dark as the Queen of the North sank out of sight, and rescued about 100 souls.

The Alaska Packer had a crew of 140, so if this ship were to be lost, the risk to life would exceed even the 2006 Queen of the North sinking. As I made my way to the ship's location, the captain radioed some details:

The situation wasn't as bad as it might sound — the day tank had been filled and was being heated as quickly as possible, but this might require an hour before the engines could be restarted and restore the Alaska Packer's engine power. In the meantime, I and the boats from Hartley Bay would need to keep the ship off the rocks.

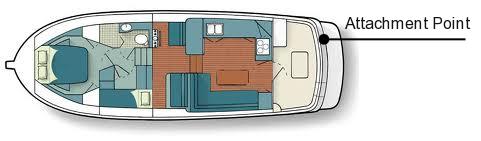

I arrived about 40 minutes after the emergency call and approached the ship's bow. A crewmember deployed a normal, fairly short dock line (see picture), which I brought on board and spliced to a much longer tow line I have for such occasions.A digression — why didn't I just use the short dock line? There are two reasons — one, the efficiency of a tow depends on the angle at which the load is pulled, and the closer to zero degrees, the better. Because of the Alaska Packer's size and the short dock line they had available, it became clear that the angle between the aft end of my boat and the ship's rail would reduce towing efficiency.

Second, when one boat tows another, the two boats should be well separated to keep the towing boat's prop wash from simply colliding with the towed boat. Remember the only reason a power boat moves through the water is because an equal and opposite momentum1 is applied to water that flows away from the stern, and if anything blocks that flow, efficiency is reduced.

My Nordic Tug 37 has a 330 horsepower engine, which until this particular day I regarded as ridiculously oversized. Given the eight million ton ship I was about to tow, I guessed I would need all 330 of those little horsepowers.

I rigged the towline and began to pull the Alaska Packer. But the best towline attachment point wasn't really centered over the prop (see diagrams), which meant my boat gradually crabbed sideways through the water, an effect I couldn't correct with the rudder.

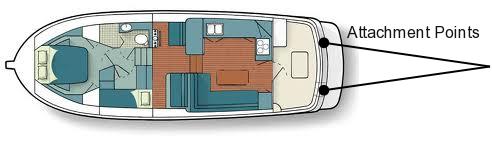

Unfortunately, after this I began to think less creatively, preoccupied by the fact that the ship might be blown against the shore and get stuck there, or even sink. Later (too late) I realized how I should have rigged the towline (see adjacent diagrams) to center the boat's force on the towline and regain normal rudder control.

But instead of realizing what I show in these diagrams, I took the captain's suggestion to rig a second towline all the way back to the Alaska Packer, which seemed a reasonable compromise to center the towing force. But with two full-length tow lines, there was a good possibility that, if I changed direction, one of the lines would go slack and be drawn into my prop.

After a few minutes of successful towing, during which I was able to bring the ship near the center of the channel, the captain asked for a 90 degree turn to speed things up a bit, and to turn and point into the wind (a better orientation). I reduced throttle and turned the wheel, and during the turn one of the tow lines went slack and was drawn into the prop.

Within 20 seconds I was alongside Aaska Packer, banging against her hull, frantically trying to cut myself away. At this point one of the Hartley Bay boats arrived and picked up my tow line, and was able to keep the ship centered in the channel for the remainder of the time until the engines became operational.

I've towed a lot of boats over the years, all successfully, but nothing remotely as large as the Alaska Packer. And almost imediately after this tow I realized how I should have arranged the towing rig — a bridle attached to two points (see diagram), able to keep the tow line centered behind the prop and the boat's thrust.

A few more items of interest:

Footnote:

| Home | | Sailing | | Alaska 2010 | |  |  |  Share This Page Share This Page |